Introduction to x86 Assembly Programming

Hello fellow pwners!

In this post, we will discuss basics of x86 Assembly Language. This is going to be a long post because a lot of concepts will be discussed.

Before we get into learning Assembly lang, there are a few important concepts to be discussed.

1. What does “Architecture” mean?

There are 2 terms to be described. Organization and Architecture .

Architecture : This is the Hardware-Software Interface present to help programmers program the hardware / processor. The set of instructions[Instruction Set], the way you can address memory, datatypes, exception mechanism etc., come under Architecture.

Organization : This deals with how a particular instruction or an addressing technique is implemented at the hardware level.

Let us take a simple example.

In the Assembly Language used to program Intel Processors, there is an instruction inc which will simply increase a particular value by 1. Syntax: inc register_name .

The Assembly Language used to program Intel processors is also used to program AMD(Advanced Micro Devices) processors. Here, the set of assembly instructions used to program them is the same. But how each instruction is implemented at the hardware level is different. The inc instruction could be implemented differently in the 2 processors.

What Architecture does it, it abstracts (or covers up) the internal hardware implementation of each instruction and provides a stable, well-defined interface in the form of an Instruction Set to programmers. The programmer need not worry about the internals of a processor. He just has to use the Instruction Set and write programs to get the job done.

Let us consider another example to get clarity.

Eg2 : To multiply 2 numbers, there is an instruction called mul .

-

Consider there are 2 processors - X and Y and both of them have this instruction mul Num1, Num2.

-

In X, Multiplication is implemented as Repeated Addition. So, X didn’t have specialized hardware to multiply 2 numbers. It used the hardware built for addition to do multiplication.

-

In Y, Multiplication is implemented using some other very efficient Multiplication Algorithm. So, Y does have a specialized hardware to multiply 2 numbers.

-

So, for a programmer, all that he knows is that there exist an instruction mul Num1, Num2 in both the processor architectures. But internally, the scene is completely different.

-

Architecture is about telling the programmer about the presence of such an instruction. But Organization deals with the internal hardware design used to design that instruction - Repeated Addition or Efficient Multiplication Algorithm.

-

In Intel and AMD Processors, the Architecture is same - meaning the Instructions are the same. But at the Hardware level, there might be differences.

-

To compare the speed of mul instruction between the Intel and AMD processors, we have to study the Organization / Internal structure of the processors.

I hope this has given some idea of what Architecture and Organization means.

In this post, we will be discussing about x86 ISA (Instruction Set Architecture) or in short, x86 Architecture.

NOTE: x86 ISA is defined for 32-bit machines. This post will cover both x86 and x86_64 / AMD64 ISA for 64-bit machines.

2. What is x86 ?

To answer this question, we will have to look into some history about Intel processors.

- Intel 4004 : Intel’s one of the first processors - 4-bit processor

- Intel 8080 : 8-bit processor

- Intel 8086 : 16-bit processor - Intel provided an Instruction Set to use Intel 8086. The 8080 was renamed to 8086 because 8086 was a 16 bit microprocessor.

- Intel 80186 , Intel 80286 were also 16-bit processors which performed better than 8086.

- Intel APX 432 was the first 32-bit microprocessor by Intel.(It was not the first ever 32-bit microprocessor to be manufactured though) . This failed as a microprocessor.

- Intel 80386 is a 32-bit microprocessor. This became very famous in the market. It made it’s mark.

- Intel 80486 : Successor of 80836.

- Then came the Legendary Intel 80586 or Pentium .

- After that, a few 32-bit microprocessors which had organizational changes were released.

- Soon after that, 64-bit processors came into market.

The point to understand is, 8086 had a 16-bit Instruction Set. When Intel introduced 32-bit microprocessors, they came up with a 32-bit Instruction Set which was an Extension of the older 16-bit Instruction Set.

8086, 80186, 80286, 80386, 80486, 80586 are the series of microprocessors. Later, they named the Instruction Set as x86 ISA where 86 stands for actual 86 in the series, the x is like a variable there. In some places, x86 ISA is also known as i386 ISA .

When 64-bit microprocessors where introduced, Intel produced the 64-bit Extensions of the x86 ISA. Along with Intel, AMD also produced their own 64-bit Extensions. The AMD’s extension was successfully accepted and Intel’s extension failed. That is why 64-bit ISA is commercially known as AMD64 . The first place I observed this when I was trying to download the Ubuntu ISO Image. There was no Intel64 option there. There were only i386(32-bit) and AMD64(64-bit). The 64-bit ISA is also known as x64 ISA or x86_64 ISA.

What does Extensions mean?

- A few new instructions are added to the Old ISA to support the new hardware design. This means, all the old instructions will be able to run on a new processor. So, I will be able to run all the x86 instructions on a 64-bit processor(there are a few exceptions) . This is called Legacy Support . One reason why this is important is because, any processor(32-bit / 64-bit) will run as a 16-bit processor (also known as real mode ) at boot time. Later after the OS starts running, 32-bit / 64-bit is supported(known as protected node ).

With the 32-bit support on 64-bit machines, we can run 32-bit programs on 64-bit machines because a 32-bit processor can be emulated on a 64-bit machine. This is very advantageous.

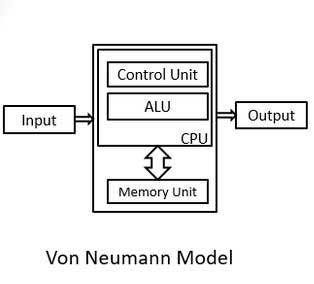

3. Von-Neumann Architecture

It is very important to understand the blueprint / architecture (architecture here means the design) of a computer system (and not ISA), because it will help in understanding why a particular set of instructions are required. This is the famous Von-Neumann Architecture , which is the design of most of the modern systems.

This above image shows that

-

There is an ALU(Arithmetic and Logic Unit) . This means it has Hardware which does Arithmetic and Logical Opeations and Bit Manipulation. So, there should be corresponding Instructions in the ISA through which we can use the ALU .

-

There is a connection between Memory Unit(RAM) and CPU. This means, there should be

-

Memory Access Instructions : which are required to load values from main memory and store back some value / results back the the main memory.

-

Instructions which support different addressing techniques. (Will talk about this in detail later in this post)

-

Some memory manipulation instructions.

-

-

Control Instructions used to make jumps, Function Calls, Returns, Software Interrupts etc., easier.

-

There are many complex instructions in x86 ISA which help the programmer as he can get more work done with fewer lines of code.

-

There are few microprocessors which support direct access to secondary memory(Hard Disk). So, there will be instructions to use that facility. But most microprocessors would not support this access to secondary memory because it takes a huge toll on it’s performance. Check this Link out. In general, CPU / Processor accesses Main memory and there is hardware designed to do that.

With some important basics covered, let us begin our discussion on x86 ISA .

4. x86 and x86_64 ISA

Before moving to instructions, we have to understand what a Register is.

Register:

-

A Register is a small storage space on the chip of the microprocessor. Generally, there will be multiple registers on the chip.

-

As this is present on the chip, the access time(time taken by the processor to read / write data stored in a particular register) is very less (Access speed is extremely high).

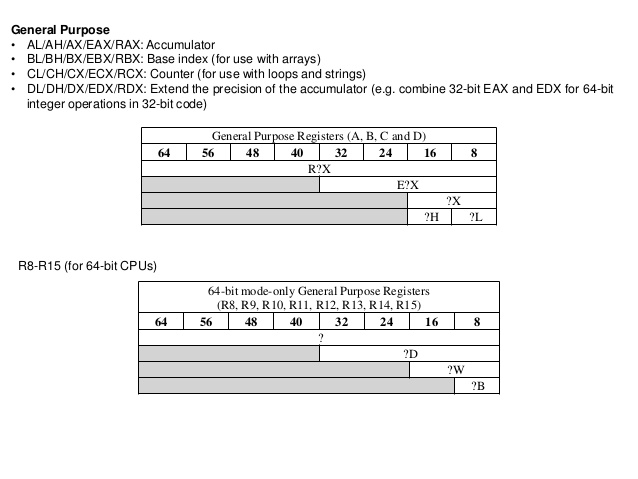

a. The x86 Architecture provides 8 registers, each of size 32-bits / 4-bytes . They are

- eax : The a stands for accumulator . An accumulator is a register which is used to store results of certain operations(Eg: Return value of a function is stored in eax).

- ecx : c stands for counter . It can be used as a counter in loops.

- edx : d stands for data .

- ebx : b stands for base . This is the Base Register. A base value for a particular operation can be stored in ebx.

- esi : Source register in string operations.

- edi : Destination register in string operations.

- ebp : Base Pointer

- esp : Stack Pointer

These registers are known as ( GPRs / General Purpose Registers) though ebp and esp are almost never used for general purposes. They have very specific purposes.

Along with these registers, there are 2 more special purpose registers known as eip/ Instruction Pointer and eflags .

b . The x86_64 architecture has 16 GPRs each of size 8 bytes . They are rax, rcx, rdx, rbx, rsp, rbp, rsi, rdi, r8, r9, r10, r11, r12, r13, r14, r15 . This register ordering is important.

-

The first 8 registers are direct 64-bit Extensions of their corresponding 32-bit registers. There are 8 new registers introduced to the ISA.

-

There are special purpose registers rip and eflags . Yes, eflags remained eflags and did not change to rflags.

Note:

- When 8-bit processors came into market, the name of registers were a, b, c, d .

- They were renamed as ax, bx, cx, dx for 16-bit processors. The x stands for extended.

- Then again when 32-bit processors came, the 16-bit Instruction Set was extended. The e in any of those 32-bit registers means extended.

- The r simply stands for register.

-

There are instructions in x64 ISA (for legacy / backward compatibility) which are used to access the lower 32-bits , lower 16-bits and the upper 16-bits of lower 32-bits of all the registers.

-

The eflags is a set of status bits. Each flag has a value of 0(cleared / not set) or 1(set) . Important flags are

-

zf : The zero flag. This is set when the result of an operation is zero. Else, it is cleared.

-

cf : The carry flag. This is set when the result of an operation is too small or too large for destination operand. Else, it is cleared.

-

sf : The sign flag. This is set when the result of an operation is negative. If result is positive, it is cleared. It is the same as most-significant bit of the result’s(2’s complement representation).

-

There are many flags other than the ones mentioned here. This webpage gives details about every flag.

-

-

The eip (rip in x64): Instruction Pointer :

-

This register stores the Address of the next instruction to be executed.

-

This register is of great importance for security folks because in presence of security bugs, the bad guys can gain control of eip and execute arbitrary code.

-

-

Apart from all these registers, there is one more set of registers known as Segment Registers . The segment registers present (in both 32-bit and 64-bit processors) are

- cs : Code Segment, Contains Starting Address of Code Segment

- ds : Data Segment, Contains Starting Address of Data Segment

- ss : Stack Segment, Contains Starting address of Stack Segment

-

es : Extra Segment

-

fs and gs : 2 more segment registers which are used for special purposes. f and g are simply kept because in 16-bit processors, there were ss, cs, ds, es . They added 2 more registers and named them fs and gs.(like c, d, e, f, g).

- In 64-bit processors cs, ds, ss and es are forced to 0. But fs and gs are used for special purposes by the OS. So, they may be non-zero.

NOTE :

-

All the registers except Instruction Pointer(eip / rip) and eflags are available for a compiler to use. The compiler can use these to convert code written in high-level language into assembly language.

-

These are not the only registers in the processor. These are the registers visible to the program / compiler. A few examples of such non-visible registers are

-

There are many General Purpose Registers which are not visible to programmer / compiler, which are used to increase performance of the processor.

-

There are a huge number of Registers used for system purposes. One such set of registers is Control Registers . They are named cr0 , cr1, cr2, cr3 . These registers help in implementing a memory management technique known as paging at the hardware level.

-

5. Different syntaxes of x86 Assembly Language

There are 2 syntaxes: AT & T and Intel Syntax.

-

AT & T Syntax :

- Instructions are of the form Instruction Destination, Source .

- Eg: movl $101, %eax

- Every constant begins with a $

- Every register is preceded with a %

-

Intel Syntax :

- Instruction are of the form Instruction Destination, Source , similar to mov rax, rbx which means move the contents of rbx(source) to rax(destination) .

This webpage gives clear differences between the 2 syntaxes. More differences come when memory access instructions are used. The At&T Syntax looks very cluttered, with extra symbols. Intel Syntax is plain and simple. Only catch in Intel Syntax is that the first operand is destination and second operand is source .

We will be using Intel Syntax throughout the post.

6. Assembler:

-

Because we will be writing direct assembly code, we do not require a Pre-Processor and a Compiler.

-

We just need an Assembler and a Linker .

-

We will be using the nasm (Netwide Assembler), an awesome opensource assembler which can generate object files of multiple formats.

-

As we are doing all this on a Linux machine, we will use the default Linker ld .

-

To install nasm on Ubuntu,

$ sudo apt-get install nasm -

Linker will already be present in the system.

7. Operands:

-

Most of the instructions operate on Operands. These operands can be

-

Registers : These are mostly the general purpose registers discussed above. In a few special cases, it could be the segment registers also.

-

Immediate Values : These are actual numbers like 100, 0x80, 0x1234 etc.,

-

Addresses : There are 2 ways to represent Addresses.

- A value: Sometimes, a direct number which is a valid address (Like 0x400000) is used.

- A Pointer: The address is loaded into one of the registers and then used. How this is done is explained in the Datatypes section.

-

8. DataTypes:

This is very important part of the post. Go through this again and make sure you understand it properly.

At the assembly level, we will be dealing with bytes. Datatypes like char , int , long int etc., are not present at assembly level. So, these datatypes should be converted to assembly code. This is done by accessing the specific number of bytes a particular datatype in C represents .

Eg1:

-

In general, size of int = 4 bytes. At the assembly level, there is not integer datatype. We only have a stream of bytes.

-

Suppose a is an integer(int) C variable, whose address is loaded into rbx (At the assembly level) .

-

So, if you want to load integer to another register(say rcx), this is how its done.

mov ecx, dword [rbx]- mov is the instruction.

- ecx is the destination register.

- dword means double word which is 4 bytes.

- The instruction tells the assembler to consider rbx to be a Double word pointer. That is, assume that it points to 4 bytes. So, when it is used in an instruction, 4 bytes pointed by rbx is loaded.

Eg2:

-

Consider another example to get the concept right. Let b be a C variable, which is of type long int . In a 64-bit machine, sizeof(long int) = 8 bytes . How is this represented at the assembly level?

-

Suppose you want to add an immediate value of 0x123 to this variable b. Suppose address of b is present in rax . This is how its done.

add qword [rax], 0x123- add is the instruction.

- 0x123 = Immediate value

- qword means a quad word which is 8 bytes.

- This instruction tells the assembler to consider rax to be a Quad word pointer. That is, consider the first 8 bytes pointed by it. So, when it is used in this instruction, all the 8 bytes are taken, 0x123 is added to it and then put back into the memory.

Let us put these concepts in a more formal manner.

-

How is size of data measured at assembly level?

- 1 byte is the smallest piece of memory which can accessed.

- word stands for 2 bytes .

- dword / double word stands for 4 bytes .

- qword / quad word stands for 8 bytes .

-

These are the data sizes supported by the hardware. This is the reason why datatypes in C are of the size 1 byte, 2 bytes, 4 bytes, 8 bytes.

-

The following are the methods to access memory:

-

byte[REG] : This tells the assembler to consider REG as a byte pointer. That is, it is pointing to only single byte . Any operation performed with this as the operand will take only 1 byte directly pointed by the address in REG .

-

word[REG] : This tells the assembler to consider REG as a word pointer. That is, it is pointing to 2 bytes . Any operation performed with this as the operand will take 2 bytes pointed by the address in REG .

-

dword[REG] : 4 bytes

-

qword[REG] : 8 bytes(Applicable only to 64-bit machines)

-

-

One very important thing to remember is, we have to specify data sizes in this manner, when we use nasm as the assembler. There are other assemblers like masm(Microsoft Assembler) , tasm(Turbo Assembler) . This is Intel Syntax. A few variations like byte ptr instead of just byte is used by disassemblers, debuggers etc., but they all mean the same .

9. Instructions:

With all the basics like Operands and Datatypes covered, let us now understand what instructions does the x86 ISA offers us.

Instructions can be broadly classified into 3 types:

- Arithmetic and Logical Instructions

- Memory Access + Data Movement Instructions

- Control flow Instructions

Arithmetic and Logical Instructions:

-

add :

-

The general syntax of add is as follows:

- add Reg, Reg

- add Reg, Imm

- add Mem, Reg

- add Reg, Mem

- add Mem, Imm

-

Examples:

-

add rax, rbx : Adds value in rax and rbx and stored it back in rax. rax = rax + rbx

-

add rax, 0x123 : Adds 0x123 to value in rax and stores it in rax. rax = rax + 0x123

-

add dword [rbx], eax : Adds value in eax with 4 bytes at memory pointed by rbx. The result is also 4 bytes, stored back at the memory pointer by rbx. (Refer Datatypes Section to know what dword means)

-

add eax, dword ptr[rbx] : Adds value in eax with 4 bytes of memory pointed by rbx. Stores back the value into eax.

-

The other 2 are similar in syntax.

-

-

-

sub : The Syntax is very similar to add instruction.

-

imul : Integer Multiplication

-

imul can have 2 / 3 operands.

- imul op1, op2 : op1 and op2 are multiplied and then stored back in op1. op1 must be a register.

- imul op1, op2, op3 : op2 and op3 are multiplied and then stored back in op1. op1 must be a register and op3 must be an immediate value.

-

-

There is idiv instruction used for integer division.

-

or, xor instructions do bitwise operations between 2 operands. The pair of operands are the same as that for the add instruction.

-

inc : Increment by 1

- inc op1 : op1 can be a Register or a memory location.

-

dec : Decrement by 1

- dec op1 : op1 can be a Register or a memory location.

These are the instructions which are used in mostly every program. Let us now move to the data flow / memory access instructions.

Data Flow Instructions

There are basically 4 instructions - mov, lea, push, pop .

-

mov : Though the name of instruction is mov, it actually does not move data, but it copies data from source to destination.

- mov op1, op2 : Copies data in op2(source) into op1(destination).

-

These are the variations in using operands.

- mov Reg, Reg

- mov Reg, Imm

- mov Reg, Mem

- mov Mem, Reg

-

mov Mem, Imm

- There is no memory to memory move instruction. It has to happen with the help of a register.

-

Reg can be any general purpose register. Under special conditions, segment registers are also used.

-

Mem has to be given some explanation.

-

At the assembly level, memory is accessed only through pointers. That is, the memory address is loaded into a register and then it is accessed. In some cases, direct valid addresses are used as well.

-

Accessing a char variable:

-

Suppose we have a C variable char a = ‘x’ . a is a character variable. We know that a character is of size 1 byte . At the assembly level, this is how it is accessed.

-

Load the address of variable a into any register(say rax).

-

byte [rax] : Refers to 1 byte of memory pointed by rax.

-

mov bl, byte [rax] : Copies 1 byte pointed by rax into bl .

-

-

Accessing a short int variable:

-

Suppose we have a variable short int s = 123 . The size of short int is 2 bytes . At the assembly level, this is how it is accessed.

-

Load the address of variable s into a register(say rcx).

-

word [rcx] : Refers to 2 bytes of memory pointed by rcx. As size of variable s is 2 bytes, this word [rcx] points to s .

-

mov ax, word [rcx] : Copies variable s into ax.

-

-

Accessing an int variable:

- mov edx, dword[rcx] : Copies that int variable pointed by rcx into edx.

-

Accessing a long int variable:

- mov r9, qword[rcx] : Copies the 8 bytes pointed by rcx into r9.

-

-

If you observe the mov statements, the size of both the operands are always same . This is very important when using assembly language. If there is a size mismatch, it pops up an error.

- Consider mov edx, dword[rcx] : edx is 4 bytes, dword is 4 bytes. This instruction cannot be mov rdx, dword[rcx] because size of rdx is 8 bytes, but dword is 4 bytes.

NOTE : This type of size matching operands is a part of many instructions. Even while using add, size of both the operands has to match. In Intel Syntax, the size matching is conveyed to the assembler using byte, word, dword, qword.

- push :

- Syntax: push op1

- Pushes the operand op1 onto the stack.

- In 32-bit machines, the stack is 4-bytes aligned . This means, the whole stack memory is made of chunks of 4 bytes .

-

An example would help to understand the concept better. Take a look at this sequence of instructions.

mov at, byte [rcx] push al- al is 1 byte long. But when al is pushed, it is pushed as 4 bytes.

- In 64-bit machines, the stack is 8-bytes aligned . This means, the whole stack memory is made up of chunks of 8-bytes .

- pop :

- Syntax: pop op1

- This instruction pops the value at the top of the stack into op1 .

- In 32-bit machines, op1 can be any 32-bit GPR or dword memory space .

- In 64-bit machines, op1 can be any 64-bit register or qword memory space .

- In 64-bit machines, pop rax is valid but pop eax is invalid.

- lea : Load Effective Address

- Syntax: lea Reg, [Mem].

- Loads the Address of the Mem .

-

mov Reg, Mem does the same thing. But lea is designed for this purpose.

- mov rax, str : Loads the address of variable str into rax.

- lea rax, [str] : Loads the address of variable str into rax.

-

In 32-bit machines, size of an Address is 4-bytes . So, Reg should be a 32-bit register. It cannot be any pseudo-registers like ax, al etc.,

- In 64-bit machines, size of an Address is 8-bytes . So, Reg should be a 64-bit register. It cannot be any pseudo register like eax, ax, ebx etc.,

Control Flow Instructions

Under normal conditions, the eip / rip takes care of control flow of a program. eip / rip stores the Address of the next instruction. But this does not work if there are conditional statements, loops, switch cases in our C program. There should be some instructions to jump to a particular location if a condition is satisfied.

- cmp : Compares 2 operands.

- Syntax: cmp op1, op2

- Checks op1 with respect to op2 and sets the appropriate flag(in eflags).

- jmp and it’s derivatives:

- Syntax: jmp Addr

- The Address can be a number which represents a valid address. Generally, it is a Label .

-

This instruction is like goto in C.

- Eg: jmp _func : _func is a label which will be replaced by an address when the object file is linked.

- Conditional jumps :

-

There are many conditional jumps like

- je - Jump if op1 == op2

- jne - Jump if op1 != op2

- jle - Jump if op1 <= op2

- jge - Jump if op1 >= op2

- jg - Jump if op1 > op2

-

jl - Jump if op1 < op2

-

All these instructions check the flags set by the cmp instruction.

-

Example: Suppose rax = 12, rbx = 0

cmp rax, rbx jge _label -

It’s C equivalent is something like this:

if(rax >= rbx) goto _label

- call : TO call a function

-

Syntax: call function_name

-

The call instruction is a sequence of 2 other instructions.

push return_address jmp function_name

- ret : Executed by callee function to return back to caller function.

-

Syntax: ret

-

ret actually means

pop hidden_reg jmp hidden_reg -

ret is called only when the callee function is done executing and return_address is the only thing present in the stack frame. So, pop hidden_reg pops the return_address into the hidden_reg .

- jmp hidden_reg jumps to the return address, which mostly is the next instruction in the caller function.

I think we are done with most of commonly used assembly instructions.

10. Declaring variables in nasm

nasm hass it’s own syntax to declare variables. Some of the most common ways to declare variables are discussed here:

-

All these declarations happen in the data section .

- var1: db 0x12 - var1 is 1 byte defined to be 0x12

- var1: dw 0x1234 - var1 is a word variable defined to be 0x1234

- var1: dd 0x120a0b3c - var1 is a double word defined to that constant.

-

var1: dq 0x1342322434234234 - var1 is a quad word defined to be that constant.

- str: db “Hello world, I am learning assembly”, 0x0a, 0x00 - This is how strings are defined. 0x0a is \n and 0x00 is NULL . Every string had to be terminated using a NULL .

-

Uninitialized variables:

- buffer: resb 1000 - Reserve 1000 bytes.

- buffer: resw 1000 - Reserve 1000 words - 2000 bytes

- buffer: resb 1 - Reserve 1 byte - probably to store a character.

- buffer: resd 1 - Reserve a double word - probably store an integer.

NOTE : Just a reminder, there are no datatypes like char, int etc., These are just array of bytes. We have defined int to be 4 bytes. So, we can reserve a dword in memory and store something there, which we call it an integer.

Will all the basics covered, let us write our first assembly program.

11.PRACTICALS

There are 2 programs. One is a simple Hello World program. Other is a bit complex as I have tried to use many of the instructions we just discussed.

Program1 - Hello world!

section .data

str: db "Hello world", 0x0a, 0x00 ; Defined str

str_len: equ $ - str ; str_len = Length of str

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 0x04 ; 0x04 is the system call number for write()

mov rbx, 0x01 ; 0x01 is the file descriptor for STDOUT

lea rcx, [str] ; Load Address of string str

mov rdx, str_len ; Load the length of string

int 0x80 ; Issue a software interrupt

mov rax, 0x01 ; 0x01 is the system call number for exit()

mov rbx, 0x00 ; 0 is the argument for the syscall

int 0x80 ; Issue a software interrupt

EXPLANATION:

-

section .data : This section has all initialized and uninitialized global variables.

- str points to the string we want to print.

- str_len stores the length of the string.

-

section .text : This section contains all the code.

- _start function is compulsory. The linker will search for this function as this is the entry point of any executable.

-

Execution is a system call.

- System call number is loaded into rax register.

- First argument of the system call is loaded into rbx.

- Second into rcx

- Third into rdx

- If there are more arguments, they would go into rdi, rsi.

- int 0x80 : int stands for interrupt (Do not get confused with int datatype). 0x80 is the interrupt vector table entry. So, the handler at the 0x80th entry should be invoked.

Eg:

Example 1:

- System call number for write() = 4. That is why, mov rax, 0x04 .

- The first int 0x80 executes the write() system call.

-

Syntax of the C wrapper function for write() is,

write(int fd, void *buf, unsigned int no_of_bytes)

-

First argument is file descriptor of the file we want to write into. We want to write “Hello world” onto stdout => fd = 1 .That is why, mov rbx, 0x01.

-

Second argument is pointer to buffer . Our string is pointed by str. So, lea rcx, [str] .

- Third argument is number of bytes to be written. We want the whole string to be written. So, mov rdx, str_len .

int 0x80 : Asking OS to handle this system call.

Example 2:

- The second int 0x80 executes exit(0) system call.

- System call number for exit() = 1 => mov rax, 0x01

- First argument = 0 => mov rbx, 0x00 int 0x80: Asking OS to handle this system call.

ASSEMBLING AND LINKING IT.

-

The name of the source file is hello.asm

-

This is how you get an executable from the .asm file.

$ nasm hello.asm -f elf64 $ ld hello.o -o hello $ ./hello

-

The above instructions will generate an executable named hello .

-

If we want 32-bit executables, we can go for elf32 option instead of elf64 .

-

-f stands for format : Specifying the format of the object file to be generated.

-

ld is the linker. It takes in hello.o, the object file generated by nasm and generates an executable.

-

Then ./hello to run the executable.

I hope you have understood what are the sections present in an nasm assembly sourcefile, how are the variables declared, how nasm and ld are used to generate the executable.

Program 2 - hello2.asm

This is also a Hello world program, difference is, we will write a function to print it, and it will be printed character by character with the help of a loop.

-

Link to the sourcefile.

-

The output of the hello2.asm is like this.

~$ ./hello2 H e l l o w o r l d ~$ -

Just follow the steps given in example1 to generate the executable.

-

Slowly go through the source code . Go through each instruction and compare with what we discussed.

12. A few more interesting things!

Segmentation

In a 16-bit processor, the length of an Address was 16-bits. So, total number of addresses possible were 2^16 addresses = 65536 addresses. As memory was byte addressable(every byte has a unique address), the maximum memory which could be addressed by a 16-bit processor was 65536 bytes. In theory, this is correct. But, a few addresses will be given to hardware. So, essentially maximum memory which could be addressed by a 16-bit processor was less than 65536 bytes.

There was huge need to increase the maximum memory addressable because programmers needed more memory to write bigger, sophisticated software. Then, Intel came with a hack known as Segmentation .

- In Segmentation, an address looked like this: Base Address : Offset .

- Offset could range from 0 to 15 .

-

Example: Base Address = 0 and Offset could range from 0 to 15. So, with 1 Base Address, the processor can address the following 16 bytes.

- 0:0, 0:1, 0:2, 0:3 , ……. , 0:15

-

In general,

- BaseAddress:0, BaseAddress:1, BaseAddress:2, …….. , BaseAddress:15 .

-

So, with 65536 / 2^16 BaseAddresses, processor now could address (2^16) X 16 addresses = 1MB of memory. Essentially, it was like having a 20-bit Address, but represented in a different manner.

-

Addressing capacity was increased 16 fold. This became such a huge hit because programmers could use 16 times memory than what they were using before.

- Segment Registers were used when Segmentation was in business, but now Segmentation is out of date. But Segment Registers are used for special purposes.

Pointers and Typecasting

Now that we know how Addresses and Datatypes are manipulated at assembly Level, let us understand how Typecasting actually works.

Example1:

Suppose you have the following piece of code:

char str[] = "AAAABBBBCCCCDDDD";

char ch = (char)str;

short int si = (short int)str;

int i = (int)str;

long int li = (long int)str;

- str points to the string AAAABBBBCCCCDDDD . Suppose we load address of this string into rax . Address of ch is loaded into rbx, si into rcx, i into rdx and li into rdi.

- char ch = (char) str => char ch = (char)rax => char ch = byte [rax] => mov r8b, byte[rax] ; mov byte[rbx], r8b .

-

In the above transformation from C to Assembly, char is transformed to byte . As ch and str are both memory locations and operations between 2 memory locations are not possible directly, I have used r8b as an intermediate register.

-

As a result of this typecast, you can see that ch finally will have byte[rax] or first byte pointed by str, which is A .

- short int si = (short int)str => short int si = (short int)rax => short int si = word[rax] => mov r8w, word[rax] ; mov word[rcx], r8w .

- In the above transformation, short int is transformed to word because both are 2-bytes.

- As a result of this typecast, you can see that si finally will have word[rax] or first 2 bytes pointed by str, which is AA. It will have ascii equivalent of AA = 0x4141 .

- int i = (int)str => int i = (int)rax => int i = dword[rax] => mov r8d, dword[rax] ; mov dword[rdx], r8d .

- As a result of this typecast, i will have 0x41414141 .

- long int li = (long int)str will result in li = 0x4141414142424242 .

- These are examples of simple typecasts. The point to understand is, all pointers are just addresses. When we say a ptr is an integer pointer, it simply means that it points to 4 bytes.

To understand the concept better, let us take one more example.

Example2:

Consider this piece of code:

unsigned long int i = 0x4142434445464748;

char *str = (char *)&i;

- In this example, an unsigned long is being typecasted into a character array.

- str will point to the whole integer as if it is a character array.

- &i and str will have the same value / address because they are both pointing to the same bunch of bytes, but the way they are operated by different instructions is different.

I hope you have got an idea of how Typecasting works.

A Note on how languages developed over the years

-

When the computers were first invented, there were no tools like compilers or assemblers or there was no Instruction Set for a processor for that matter. Instructions were fed in their binary form. Literally, 0s and 1s were being fed into the computer.

-

It was too tedious and the number of errors made were really high. Then idea of Instruction Set came in. An Instruction Set was required because there was a need for a well-defined interface through which a processor could be programmed. So, for every processor, an Instruction Set was defined and Assembly Language was born.

-

Each assembly instruction was fed into the machine now. Even this became a tedious job as programmers went to write bigger programs. Then came Assembler - A tool which converts a set of assembly level instructions into machine code.

-

Major disadvantage of using assembly language is it is not portable across processors. Suppose I write a Database in x86 Assembly Language, then that can be run and thus used only on Intel Processors. It could not be run on any other processors like SPARC, PowerPC etc., So, programmers had to write the same software again and again in different assembly languages to give support for different processors.

-

The UNIX Operating System was first written in Assembly Language. This was obviously not portable. Then the C Programming Language was invented and the whole OS was re-written in C. What we needed is a tool that converts C code to assembly code, which is the compiler.

-

What we had to do is, develop different compilers for different architectures. Every architecture will have it’s respective compiler. So, when a program is written in C, if I want it to run on Intel processors, I would use a Compiler that would convert C code to x86 assembly code. If I want it to run on a mips processor, I would a Compiler that would convert C code into mips assembly code. So, Compilers became very successful because code was becoming portable because of them.

-

Now, we have Python which is an Interpreted Langauge. It’s Interpreter is written in C, which is a compiled language. So, we have gone one more level up from compiled languages. Even Java’s JVM(Java Virtual Machine) is written in C.

-

There is a language called Haxe. It’s compiler can give output in C++, Python, C#, Java. This is a language which is one level higher than Interpreted languages in terms of Level of Abstraction.

This is how languages have evolved. You can observe that the level of abstraction has increased so much - From 0s and 1s to languages which compile to give sourcecode in other languages.

That is it for this article. I learnt a lot while writing this post. I hope you have understood basics of assembly programming.

Thank you for reading :)

Go to next post: Memory Layout of a Process

Go to previous post: What does an Executable contain? - Internal Structure of an ELF Executable - Part1